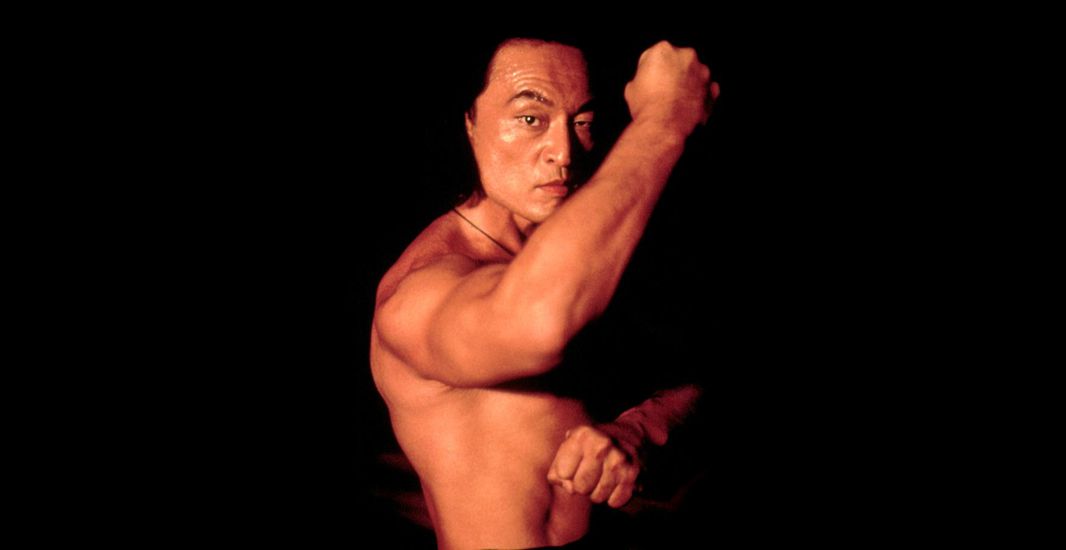

Cary Tagawa is rapidly becoming one of the most recognized faces in Hollywood. He was the soft spoken bad guy who co-starred opposite Sean Connery and Wesley Snipes in “Rising Sun,” and his role of Shang Tsung in Mortal Kombat made him a cult hero. Tagawa’s dramatic looks and on-screen charisma, coupled with his martial arts skills, has put this actor on Tinsel Town’s “A” list.

Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa began his acting career in 1985 at age 36 as an extra in “Big Trouble In Little China.” His next film was “Armed Response,” followed by a major role in “The Last Emperor.” Tagawa was on a roll, and this during a time when Hollywood was looking for Asian bad guys. With his dramatic facial features and years of martial arts training, Tagawa quickly cashed in on his talents.

“I was very fortunate that it was the Asian’s turn to be bad guys,” said Tagawa about his career. “I think the bad guy is very important in a film. My martial arts background was also a big plus in getting some the roles I’ve had.”

One has only to watch Tagawa in action to know that he is the real deal when it comes to the martial arts. He may not flaunt his skills like some celluloid black belts, but I can tell you from first hand experience, that this is one actor who isn’t acting when it comes to the martial arts.

“I was born in Tokyo and began training in Kendo when I was in Junior High School,” recalled Tagawa. “Then when I was five we moved to Fort Brag, NC; and that’s when I got my first real lesson in how to use the martial arts.”

An army brat, Cary found himself moving every time his father transferred to a new base. When his dad was sent to the States, Cary left a loving and supporting family in the land of the rising sun for the discord and racial tensions that flourished in the land of the free

“Being Japanese and living in the south during the 50’s was pretty tough,” said Tagawa. “That’s when I first recognized the need for martial arts as a way to survive,” joked the good natured actor. “However, my definition of the martial arts may be different from that of other people.”

Instead of squaring off with the rednecks and bullies who taunted and threatened him, Tagawa fought them with his mind instead of his fists. Without resorting to violence, Tagawa found ways to re-direct their anger, thus avoiding unnecessary conflict.

“There are no winners in a fight,” said Cary. “It’s always better to resolve a situation peacefully.”

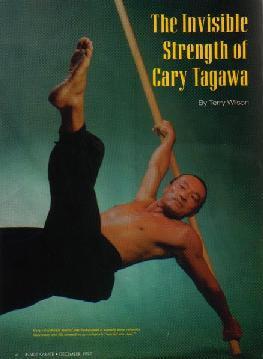

Tagawa and I sat under a palm tree for several hours discussing the invisible force of chi and how to access that strength. For him, this theory isn’t only a philosophy, it is also a science that he has studied for decades.

“I think the basic component in the study of the martial arts is the study of energy,” said Tagawa. “I view energy as a source of connecting to a part of us that isn’t available by simply looking at logical reasons. It is also different from the typical Western way of thinking, which has no connection to nature.”

Understanding who you are, why you are, and knowing what purpose you serve in life, is the foundation from which Cary builds his martial arts philosophy. To help promote harmony between mind, body and spirit, Tagawa created his own system called “Chun-Shin.” Translated this means: “to be centered inside your heart and mind.”

“Before teaching the physical applications of the martial arts, I begin by teaching the energy of the art,” said Tagawa. “There are a lot of martial artists who physically know forms who are also curious about what else is available, I want to tap into that curiosity and bring that aspect to the martial arts.”

With my curiosity peaked, Tagawa offered to give me a lesson in his system of Chun-Shin, which I eagerly accepted. It was unlike any martial arts workout I have ever experienced. We began with a breathing exercise to unblock clogging energies from my system. As I inhaled and exhaled, Cary maneuvered my aging frame into a variety of positions. Some were sitting, others standing, and a few that made me look like a human pretzel. During these maneuvers, Tagawa pushed and rubbed different points along my nervous system with his elbows and fingers. The lesson lasted well over 90 minutes, when we were through my body felt and reacted as if it was 10 years younger. In fact, for years I’ve been nursing a judo leg that has been sorely abused; by the end of our session, I looked like a Tae Kwon Do guy. My once hard-to-stretch leg was now limber and pain free. It had been years since I was able to flip off a high roundhouse with that leg. By the time Cary had finished with me, I was snapping kicks with the best of ’em. Most importantly though, my chi or energy field was very strong. Everything around me became centered and calm; it was amazing. The overall effect of this workout stayed with me for about a week. What I had taken was by first baby step toward the martial arts “light at the end of the tunnel.” For Tagawa, that light had been guilding him for years, both in his personal life and his career.

“Another thing I have discovered about the martial arts, is that it gives me a choice in how to deal with different things. Through the martial arts, I can evaluate different energies. It could be by opponent, or dealing with Hollywood, or even a bully. In any given situation, you are dealing with energy. And that’s how I teach the martial arts. First, I get someone curious about the difference between using the physical force versus a mental force. Then I help them develop the inner strength we all have, but few of us know how to use.”

Tagawa has an aura of calm that surrounds him and anyone in his presence. I was with him on a frantic filming day for a new TV series. It was like a Chinese fire drill. Frantic and panic was the name of the game, except when Tagawa was around. The negative energies just melted away in his presence. Crazed producers mellowed out, frowns turned to smiles, and suddenly, harmony replaced anxiety.

I overheard a crew member ask Cary “How come everyone likes you so much?” He replied softly, “I don’t give them anything not to like.”

In the martial arts, we are all told about the importance of centering, focus, and energy control. But how many of us ever really get to that level of development? It takes decades for many martial artists to even begin to comprehend the basic principles of internal energy. Tagawa however, knew from a very early age that the true power of the martial arts came from the universe, and not from a reverse punch.

“From the age of five, I understood where the real power of the martial arts came from,” recalled Tagawa. “The core of the martial arts, the energy where it comes from, is a natural bond with people. It is a love, or concept, of humanity as a whole in which we start. A lot of times in the martial arts we go through the conflict to teach the harmony. Where I started from was harmony, then moved into conflict. The conflict Tagawa referred to was his additional training in Kendo and karate. At the age of 21, Tagawa began training traditional Japanese karate at the University of Southern California. A year later he moved back to Japan and began studying with the J.K.A. under Master Nakayama. The training was very traditional, grueling and often times brutal.

“We studied six hours a day two hour at a time,” said Tagawa. “Kata was the key to everything we did. We did kata until we dropped. Kumite was always extra. And when we fought, they put white belts in with the black belts. The first time I ever saw a double kick was when I went to block a front kick and he did a change up, landing his foot squarely against the side of my head. Getting hit like that set off a very primal impulse in me. I wanted to go back out there and get him back.”

After the cobwebs cleared, Cary bowed in for another round. It was pay back time. When his opponent got close enough, Cary let loose with a perfectly timed backhand. It landed squarely, sending his opponent crashing to the floor with a bloody mouth.

“We fought with full contact, but not full power,” explained Tagawa. “Of course back then we didn’t wear gloves or foot protectors. One thing I noticed about Japanese training is that there is no regard for anything personal. It’s all about how to get out of personal. So if you worried about your safety, you won’t commit to a technique. The Japanese care about total commitment, and that doesn’t just apply to karate students either. Everyone in Japan is committed to what they do. From the presidents of major companies to the guy who cleans cigarettes off the floor at the train station. They are committed to doing the very best at what ever it is they do. Discipline is a committment, focus is a commitment, and training is a commitment. And not only must the students demonstrate commitment, so must the teachers. That’s something you don’t see in many western dojos.”

Although Tagawa proved himself to be an outstanding fighter, the idea of being the best via a high body count was not in harmony with his definition of what the martial arts was about for him.

“I didn’t agree with that ‘let’s go out there and beat the crap out of the other guy’ mentality,” said Tagawa. “The J.K.A. wanted the world to perceive us as being the strongest style and they did this through fighting. Eventually I had a problem with that way of thinking.”

Tagawa did not feel comfortable with his school’s philosophy. He wanted to develop spiritually, so Cary sought advice from his teacher.

“That was when my concept about the martial arts changed radically,” recalled Tagawa. “When I asked master Nakayama about meditation, he replied ‘you’re young, you fight now. You meditate when you get old.’ Coming from one of the two highest ranking masters in Shotokan karate, that answer just wasn’t enough for me. It made me stop and consider what my goals were. I knew what I got from the martial arts was a deep inner peace. And that’s what I wanted to explore and develop.”

Tagawa thanked his teachers for lessons learned, packed his bag and left the team and the dojo to pursue another level of training.

“I never quit the martial arts, I just left the formal structural training,” said Tagawa. “At that time I began studying meditation, metaphysics, numerology and anything else related to any process that had some explanation of energy or the way the world works.”

It was during his quest for knowledge that Tagawa slowly assembled the pieces of what is now his system of Chun-Shin.

“My style of Chun-Shin is completely without a physical fighting concept,” explained Tagawa. “It is a study of energy and I use an 8-foot staff which makes it a little more physical than Tai-Chi or Yoga. The staff gives you a third point of balance that we normally don’t have.”

Cary went on to explain that animals like dinosaurs and kangaroos could balance themselves on their tail, freeing their other limbs for fighting or foraging. After giving much thought to the subject, Tagawa created a way to put a “tail” on his students.

“After more than 20 years I have developed the staff into a whole system where I can teach centering, focus and balance,” said Tagawa. “This gives me a third point of balance and enables me to open up a lot of energy paths. Plus it gives me a force to work against, which is very helpful.”

Tagawa doesn’t have plans to open hundreds of Chun-Shin schools or to cash in on his celebrity, although he could. He is one martial artist who merely wants to share his knowledge with others. His goal is to guide those who share an unquenchable thirst for the martial arts to the well. How much they drink, is up to them.

“My intention for Chun-Shin is to eventually become a centering point for all martial arts styles. At the core of all of us as martial artists is a desire to better ourselves. And that’s what I want to help bring about.”