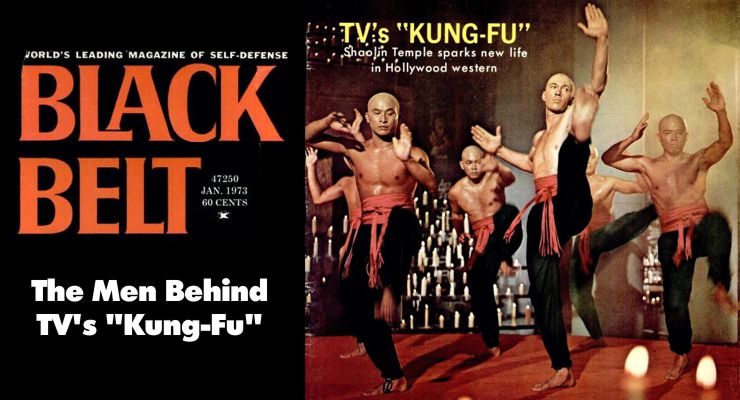

The Kung-Fu TV series was released in the United States on October 14, 2012. On this 40th anniversary of the television series we reprinted this article about the men behind the Kung-Fu TV series. The article was first published in Black Belt Magazine on January 1973. It was written by Jon Shirota. We are not certain who took the photos.

A millionaire, a dashing young star, two veteran character actors and a handful of martial artists pool their talents to put realism in a unique TV Kung-Fu Series.

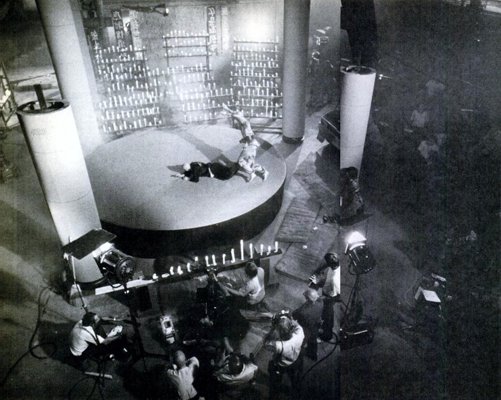

SOMEONE YELLS, “QUIET, PLEASE!” and the murmurs and movements of the camera crews, technicians, extras and visitors in Stage 16 gradually diminish. A bell rings. Suddenly, absolute silence.

“Roll!” Cameras at different angles start grinding.

“Action!”

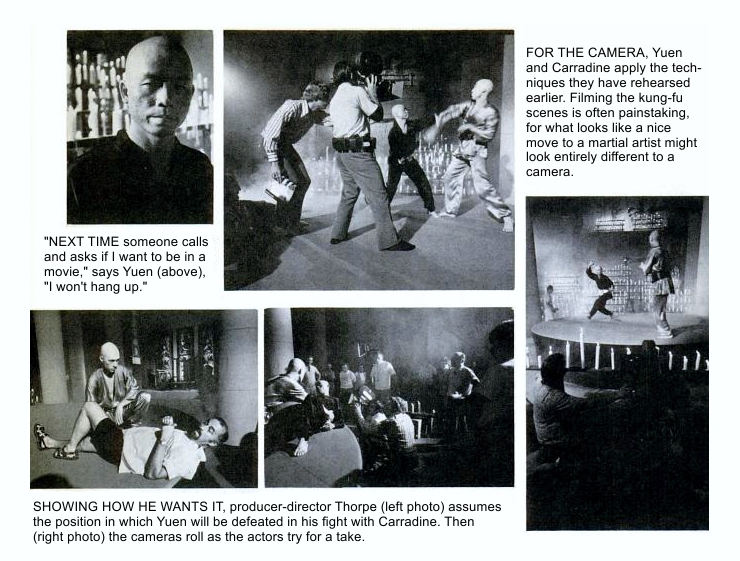

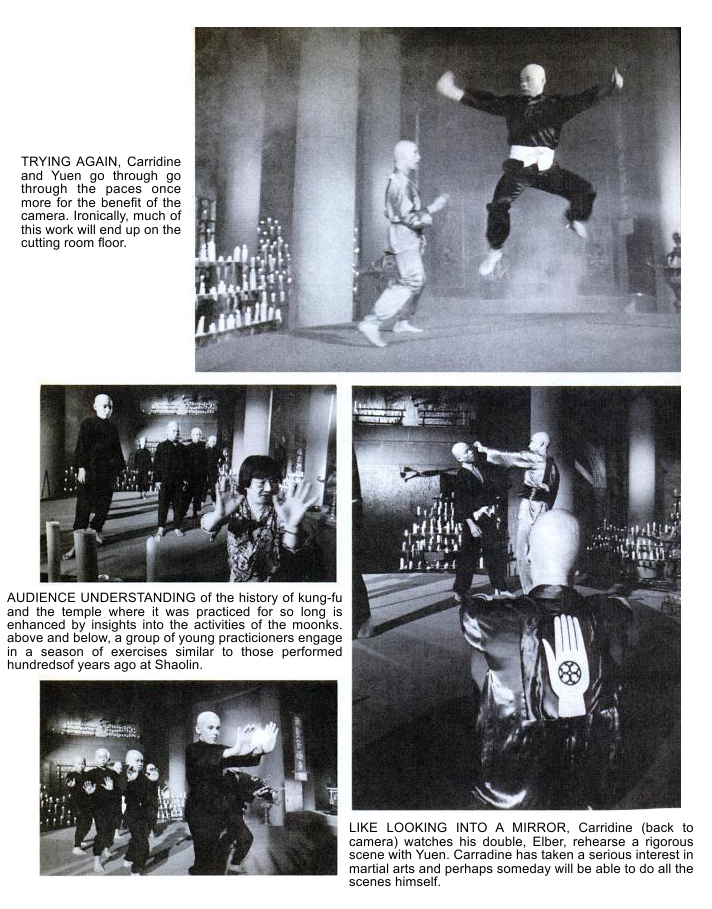

Producer-director Jerry Thorpe, lean, bearded and handsomely tanned, stands beside one of the cameras, feet firmly planted, arms folded. His keen, discerning eyes keep a steady vigil on the stage up front. Disciples Caine and Lin Wu, dressed in kung-fu regalia, advance toward each other. They stop and bow, the sadness in their expressions disclosing a reluctance to fight each other. It is a Shaolin Temple scene, myriads of candle lights flickering softly in the background, clouds of incense smoke hovering overhead, masters, disciples and students in ceremonial customs sitting stolidly around the stage.

Once the contest begins, Caine and Lin Wu forget their friendship and summon all their skills in kung-fu science to beat the other. The victor will advance to a higher order while the loser must wait another time for a second opportunity. Although they pull their punches and kicks, their executions simulate mortal combat. They assume various stances, feigning, advancing, retreating. Each step, each move, is met with counter stances, and every counter stance is followed by series of advances. The two martial artists flawlessly execute the ancient forms of kung-fu that have been a part of their lives since boyhood—the way of the eagle, the tiger, the crane, the snake and the praying mantis. Their blows are aimed at vulnerable points: the eyes, the nose, the throat and the groin. When physical exhaustion overcomes them, they rely on their inner strength, their chi, and continue the battle, each trying to outwit the other, each looking for an unguarded weakness.

“Cut!”

The cameras stop immediately. Thorpe fondles his beard a moment, pondering, undecided, his eyes gazing down at his sandals. Looking up, he says, “That was good. But let’s do it once more.”

The scene is repeated, and this time the reaction is different. A warm smile flashes across the producer-director’s face. “Great! Terrific! That’s a print!”

THE RAISING OF CAINE

The suspenseful. action-packed scene is from “Blood Brother,” one of the segments from Kung-Fu, the new television series produced at Warner Brothers Studio. Response to the pilot, shown last season as an ABC Movie of the Week, was so overwhelming that the studio decided to make it into a series. The basis of the story remains as initially presented: Caine, a fugitive from Chinese Imperial justice of the late 1800’s, roams through the wild American West, trying to find a place for himself in a world that neither understands nor ‘accepts him. He is a Shaolin priest who has escaped from China after killing the nephew of the Imperial House. Although his act had been in self-defense, a reward has been offered for his capture, and bounty hunters are after him.

Putting together a series like this one can be a very tricky task. Action scenes (which, in the case of Kung-Fu, are enlightening as well as entertaining) must be delicately blended together with the storyline. They must complement the history, philosophy and drama contained in the rest of the script, not detract from them.

Above all, the action scenes must be totally believable or the viewers will laugh when they should be intrigued, and fall asleep when they should get involved. They will not sit through a kung-fu fight scene that reminds them of a boxing movie in which the fighters’ stances were awkward and their blows stiff and ineffective.

Fortunately, the movements and actions in Kung-Fu are swift and natural, the blows and kicks smooth and graceful. Each movement seems to tell an ominous but engrossing story that has been handed down from generation to generation.

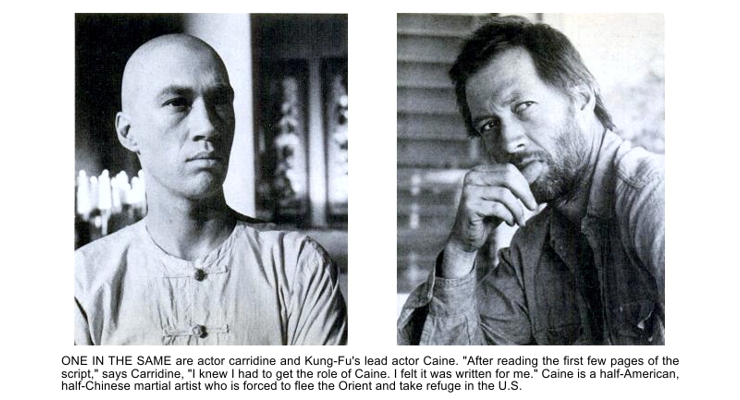

David Carradine, who stars in the series as Caine, is totally immersed and involved in his role as the stoic half-American, half-Chinese kung-fu master who, during his formative years, lived a harsh, monastic life in the Shaolin Temple. Carradine feels, sees, hears and thinks as Caine. using his body as well as his face and voice to build the characterization.

“After reading the first few pages of the pilot script, I knew I had to get the role as Caine,” says Carradine. “I felt the role was written for me.

“It was weird.” he goes on. “I had shaven my head just the week before I got the script, and the part called for a bald man. And, just the day before I got the script, I found an old pin with Oriental designs. I had it on when the script was handed to me.

“No, I’m not superstitious… well, maybe just a little. How can you explain these things?”

Carradine says he realized right away that Kung-Fu wasn’t just another Oriental mystery. “It had historical value. We know Chinese laborers played a big part in building rails through the western half of this country. How many of us really know how badly they were abused, mistreated and sometimes even murdered?”

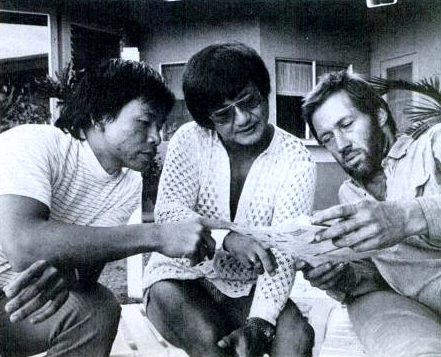

With characteristic frankness, Carradine admits he never had martial arts training before the series. “Now that I know more about it, I really like it,” he says. “I plan to keep on training. I have to, or my teachers—David Chow and Kam Yuen—will keep beating me.”

Tall, lean and sinewy, this talented son of well-known character actor John Carradine appears to be a natural athlete. An ardent believer in physical fitness, he spends a great deal of his time running barefoot and exercising in surroundings where nature’s habitats are yet untouched and unspoiled by human intrusion. An accomplished musician as well as a promising young actor, he goes on periodic fasts, which, he believes, not only keep his weight down, but also sharpen his mind.

“Kung-fu seems to serve a dual purpose. too,” he says. “It keeps you both physically and mentally sharp. Before training for the Mies, 1 used to feel sluggish. After a couple weeks of training, I began to feel much better. I also began to feel a nice, rhythmic flow to my movements. Of course, the more I trained the better I felt.

“This, however, doesn’t mean I know all there is to know about kung-fu. Far from it. The more I learn the more I realize how little I know about it.”

IN CHARGE OF REALISM

The man primarily responsible for the realistic fight scenes in which Carradine performs is the series’ technical director, David Chow. And as the enemy in the pilot’s climactic fight scene, Chow evoked the best from his protege.

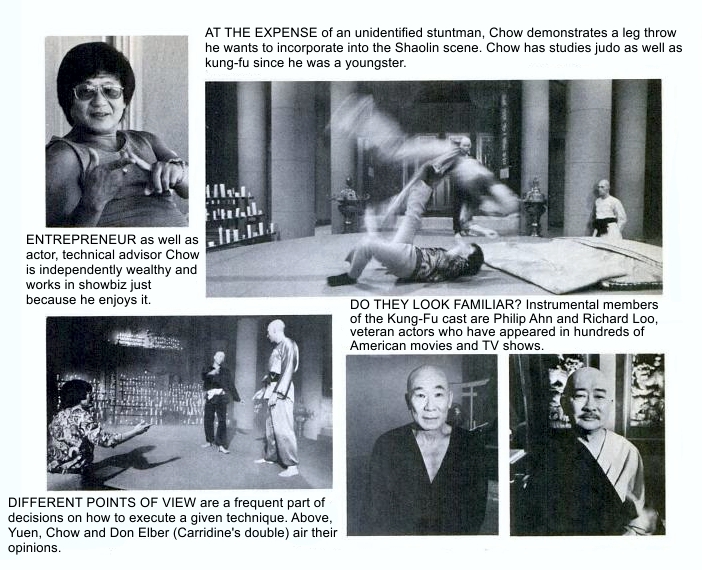

Chow himself is a multi-dimensional man with varied interests. He is a business tycoon, prize-winning photographer. sportscar racer, airplane pilot, sharpshooter, actor and, of course, a martial artist. A man of seemingly inexhaustible energy and resources, Chow attributes his success in both business and sports to a five-finger philosophy which he wholeheartedly embraces: (I) physical fitness, (2) education. (3) pride of profession, (4) monetary and emotional security. and (5) respect for friends and family. He also credits the martial arts and their philosophy for his success. “It develops willpower and the right mental attitude for meeting challenges,” he explains.

Born and raised in Shanghai, where he learned kung-fu from Tung Sung-Yee and judo from a Japanese sensei, Chow came to this country in 1950 as a student. To support himself, he opened judo classes at UCLA and gave private lessons to special police. Once, while he was giving an exhibition at a college basketball game, a TV camera focused on him long enough to arouse the interest of a movie director at Twentieth-Century Fox. Next day, the director called him to the studio and gave him a part in a movie involving martial arts. It was an auspicious debut for the young man from Shanghai.

Since then, Chow has appeared in countless movies and TV shows, both as actor and technical adviser. His more notable appearances include Flower Drum Song, The Ugly American. Bonanza, Hawaiian Eye, I Spy and The Skin Game. Acting, however, is only an avocation for Chow. After earning his bachelor’s degree at UCLA and his master’s at USC in industrial economics, he founded the Intercontinental Marketing and Trade Corporation and went on to make a sizable profit from business.

A DEMANDING JOB

As technical adviser to Kung-Fu. Chow has to travel all over California to look for kung-fu practitioners whom he feels can adapt their styles to particular parts. Once the shooting starts, it is up to him to settle differences of opinion regarding the fight scenes. The basic problem is that most of the kung-fu practitioners have never been in films before and are not familiar with the technical aspects. Some insist on more realism in fight scenes, disregarding difficult camera angles; others demand more authentic sets, disregarding budget limitations. However, says Chow, once they realize that making a film involves a collective effort by all concerned, their attitudes change and they become very cooperative.

Chow not only works with the actors, but also helps introduce new scenes to, as well as eliminate some from, the scripts. “We have to make sure the fight scenes are believable,” he says. “We do not want the public to think that kung fu is some kind of a Chinese magic or that the masters are super-human brings. We want the public to learn a little about the ancient art of kung-fu, its history, its philosophy and its applications.”

Despite the insistence on realism, there has been only one mishap, when Chow inadvertently hurt Kam Yuen when he was doubling for Carradine. “It was during the last scene in the pilot when Little Monk throws Caine down the hill and kicks him,” recalls the technical advisor. “What happened was, when I grabbed Kam and threw him over my shoulder, some dirt flew in my face. I couldn’t see for a second. When I kicked, I felt a contact. I had kicked Kim in the groin! Not too hard, but hard enough.

“No. We couldn’t stop. It was one of those scenes that had to keep rolling. Kam? He’s either one heck of an actor who believes in ‘The show must go on,’ or he can take a kick in the groin better than any man I know!”

Of Carradine himself. Chow says, “He fits the part of Caine like a glove. And, he’s a good kung-fu student. He learns fast. His movements are unbelievably fluid for a guy just starting. He trains hard for the fight scenes and spends lots of hours in the studio gym with Kam and I learning the movements and techniques. Once, when I was a little tired and wanted to take a break, he practically pleaded. ‘David, once more. Just once more.'”

YOU WANNA BE A STAR?

One of the kung-fu practitioners who. Chow says, adapted easily to filmmaking is Kam Yuen (whose given name is Liang Kam Yucn). An advocate of Tai Praying Mantis Kung-Fu Association, Kam doubled for Carradine in the more difficult fight scenes in the pilot and also appears in many of the awesome and spectacular exhibition scenes at the Shaolin Temple.

“I thought someone was pulling my leg when I got a call asking if I wanted to be in a movie,” Kam cheerfully recalls. “I told the guy, ‘Sure, I’d like to be in a movie,’ and hung up. “Next day, the guy calls me up again. Only this time, he invites me over to his home. When I drove up to the Hollywood Hills and came to his pad I thought, ‘What)! This guy might really mean it.’ That was the first time I met David Chow.”

Kam had second thoughts, however, when he found out the role called for a shaved head.

“‘No way!’ I told David. ‘I don’t want to shave my head.’ When he explained that it would mean bigger and better roles. I told him I’d think it over—like two seconds!”

Fondly running his fingers through his revitalized hairdo, which required “months to get it back to where it is now,” Kam says he’ll be more receptive to future phone calls offering him Hollywood jobs. “Next time someone calls and asks if I want to be in a movie, I won’t hang up. I might ask whether I have to shave my head, though…”

Veteran actors Philip Ahn and Richard Loo, who probably have acted in more Hollywood films than any other Oriental actors, are used to portraying bald men. In Kung-Fu, they portray Shaolin priests.

“I was very pleased when I read the pilot script,” says Ahn. “It was written very honestly. For once, a film showed how badly the Orientals in this country were treated during the early days. It also gives Westerners a better insight of the great Oriental culture.”

“It also gives the Westerners a better image of the Orientals,” adds Loo. “They (the Orientals) are not shown as the stereotyped houseboy, laundry man or cook. They get their just dues. They are portrayed as highly intelligent men with worldly knowledge.”

Ahn sees Kung-Fu as more than just another Western primarily because “it has depth. It has a wonderful social message. And, the camera work and editing are superb.”

“Of course,” concludes Loo, “much of the credit belongs to Jerry Thorpe. He’s a very understanding and sympathetic human being He knows how to get the most out of his actors. And everyone—his assistants, camera crews, technicians, extras—are always more than willing to cooperate with him.”

One of many kung-fu practitioners who have parts in the Shaolin Temple scenes is Jack Sera, a Japanese-American. Sera took up kun-fu in lieu of his ancestors’ favorites, karate and judo, for several reasons. “For one thing,” he explains, “I enjoy the philosophy and history of kung-fu. I also feel that kung-fu has more to offer me than karate or judo.”

Sera hesitates a moment when asked to give a critique of the kung-fu movements and actions used in the series. “I think the techniques are fine,” he concedes, “but the executions, at times, are wrong. On the other hand. I can see where there’s lots of problems filming the executions.”

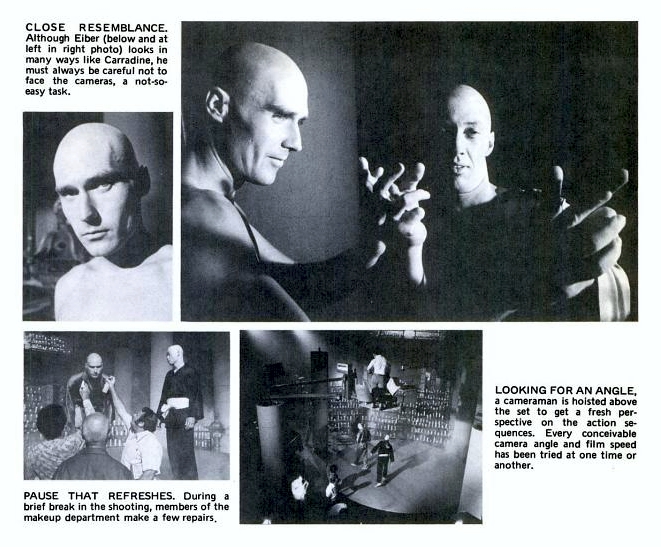

DOUBLE TROUBLE

A man who must overcome some of those problems is Don Eiber, the regular double for Carradine. Although there is a startling resemblance between the two—same height, weight and build—Eiber must always be careful not to face the camera, even during the falls. “Sometimes I forget and turn my face the wrong way,” he admits, wiping sweat and dust off his face after a strenuous fight scene in which he took several hard falls. “The falls are easy to do. but the paddings on the stage are so thin you can’t afford to make mistakes. Once, when 1 was concentrating on not facing the camera, I landed on the back of my head. I was glad it was a print. I was out of it for several minutes.”

Eiber has had many ups and downs in his relatively young life. Born and raised in Ohio. he came to California more than 10 years ago to see what the land of golden sunshine, oranges and peaches was like and also, with a bit of luck, to get into movies. He enjoyed the sunshine and ate lots of fruit, but he did not get even a nibble of stardom. Dispelling wistful dreams, he got a job driving trucks and enrolled at Los Angeles City College, then persevered on to California State University. Los Angeles, where he finally received a BA degree in drama.

During all those years he took judo lessons from his friend David Chow. After Chow discontinued his classes, he frequently invited Eiber to his home, where they worked out together. When the part for Carradine’s double became available, Chow introduced Eiber to Jerry Thorpe. Since that time, Eiber has been experiencing many more ups and downs, but this time by choice.

As wisely expressed by the venerable priest of the Shaolin Temple, many are called to the gate of the temple, but only a few are chosen. Perhaps, with a little bit of luck, the next time Don Eiber or one of the many other bit-players appearing in Kung-Fu is called to the studio gate at Warner Brothers, he will become one of the few chosen to share the tantalizing rewards of stardom.

By Jon Shirota ~ First Published in Black Belt Magazine, January 1973