On July 20, 2017, EL REY Network will air Episode 7 of Season 1 of MAN AT ARMS: ART OF WAR – Stuff That Legends Are Made Of. This was one of my favorite episodes. Not only did I get to demonstrate the featured weapon for camera, it explored a field of study that I’ve been fascinated by for years – Spanish sword. Due to my commitment to Kung Fu Tai Chi, the lion’s share of my research is dedicated to the Chinese martial arts, but in a former incarnation I was a fencer. In fact, I’m a certified Provost Master at Arms in fencing, double-certified in fact, but that’s a whole other tale. The history of European cold arms is rich, telling and well-documented. It befuddles me as to why most martial artists don’t approach fencing like the other martial arts. Bruce Lee did, but again, a whole other tale.

On July 20, 2017, EL REY Network will air Episode 7 of Season 1 of MAN AT ARMS: ART OF WAR – Stuff That Legends Are Made Of. This was one of my favorite episodes. Not only did I get to demonstrate the featured weapon for camera, it explored a field of study that I’ve been fascinated by for years – Spanish sword. Due to my commitment to Kung Fu Tai Chi, the lion’s share of my research is dedicated to the Chinese martial arts, but in a former incarnation I was a fencer. In fact, I’m a certified Provost Master at Arms in fencing, double-certified in fact, but that’s a whole other tale. The history of European cold arms is rich, telling and well-documented. It befuddles me as to why most martial artists don’t approach fencing like the other martial arts. Bruce Lee did, but again, a whole other tale.

MAN AT ARMS: ART OF WAR: Episode 7: “Stuff That Legends Are Made Of” focuses on two legendary swords – Zulfiqar, the mythical double-bladed sword given to Ali ibn Abi Talib by Muhammad himself, and Tizona, the legendary sword that the Spanish hero El Cid won from King Ali ibn Yucef in Valencia. As you’ll see in the episode, the actual Zulfiqar is lost. Tizona currently resides in the Museo de Burgos in central Spain. There is some question as to its authenticity, which we addressed while filming the episode. Some anachronisms lie in Tizona’s construction, like the guard which isn’t quite right for the period along with some other questionable details. But if it’s a forgery, it’s still from as far back as the 16th century (El Cid reigned as the Prince of Valencia from 1094 to 1099 CE). Regardless of its debatable authenticity, Tizona is a spectacular sword, so gorgeous that El Rey used it in the publicity posters by placing it in the hand of the host of MAN AT ARMS: ART OF WAR, the one and only Danny Trejo. What’s more, Tizona is arguably the most reproduced sword in the world. Before the master craftsmen and women of Baltimore Knife & Sword forged the Tizona we used in Episode 7, countless swordmakers have tackled this particular blade before. It was an honor to test their recreation for the show.

Crossing the Guard

When that promo poster came out, some amateur swordsmen, as well as a few masters, dismissed it because Danny Trejo’s finger was crossing the guard. It’s a shame because Danny’s grip was absolutely correct. We showed him how to hold Tizona properly and Danny was eager to learn. Danny explained, “In the movies, a lot of the stuff you use is kind of, ahh, I don’t want to say ‘fake’ [laughs]. It’s for the movies, you know? Now, these are real weapons. Sharp as hell. I mean, we had people cut themselves on it. If you don’t listen to the people that know what they’re doing, it’s like you will cut yourself. Even if you know what you’re doing, if you try to combine one style with a weapon from a different era, it’s not going to work. It’s not designed to do that. But I’ve really learned quite a bit. I’ve learned to really respect the weapons and really respect the people that make them and the people that know what they’re doing.”

Like I said, I’m a certified Fencing Provost Master, a Prevot d’Armes d’Escrime if you want the formal title in French (pardon my French). A Provost must master one of the three weapons of modern fencing – foil, saber or epee – and be capable of giving basic lessons in both of the other two weapons. An individual who masters all three is called a Maestro, just like a symphony conductor. Notably, this is the common term used in English from the Italian, instead of the French Maitre. The French and Italian schools dominated fencing for centuries. In the early ’80s, I went through the Fencing Master program back when it was at San Jose State University under the auspices of the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (I kid you not – back then, fencing was still considered a military tradition). The program was founded by the late Maestro William M. Gaugler, who propounded the classical Italian system implemented by the Military Fencing Masters School of Rome. The Italian school uses a traditional guard with finger rings (pas d’ane), cross guard (quillon) and ricasso (an exposed portion of the blade’s tang). All of these parts are hidden behind the bell guard. It’s an antiquated guard, no longer used in modern competition, but authentic nonetheless.

There is a Darwinian evolutionary progression for European sword hilts that begins with a long sword and ends with the modern fencing foil. One of my fellow Provost candidates, a teammate from the SJSU NCAA fencing squad, wrote his Provost thesis on this very topic: The Sword Hilt: Its Evolution from the Battlefield to the Fencing Strip. He went on to complete his training, and now Maestro Cole Harkness is one of the head proprietors of Victory Fencing Gear. In his thesis, on pages 3 and 4, he states “The guard until approximately 1350 consisted solely of a simple cross piece, with variations in length and thickness and curvature…The simple cross-hilt sword remained popular through the 1440’s, even though trends and fashions became noticable (sic) after 1350. The first datable addition to the simple cross is the addition of a ring extending downward from the cross to the ricasso. This was to protect the finger that was often hooked over the guard for a more secure grip.”

Here lies a question of the authenticity of Tizona. If finger rings don’t emerge until 1350, how does El Cid get this sword by the 11th century? Some theorize that the blade was refitted into a more contemporary hilt later. That’s not at all unheard of as sword hilts can break in battle, so consequently good blades were often refurbished with new fittings throughout history. Regardless, this demonstrates that those critics of Danny’s grip were just being ignorant. False assumptions on how to grip a sword is exactly the sort of weapon mythology we hope to dispel with MAN AT ARMS: ART OF WAR.

The introduction of finger rings was as much of a major evolutionary step for swords as when the first fish started to squirm across land. The more secure grip provided by crossing the guard led to improved thrusting capabilities. And over time, rings became more complex with artistic sweeps and cages to protect the sword hand, eventually closing together to form the bell guard. Despite the cinematic swashbuckling swordplay of the Three Musketeers, cup-hilt rapiers were most effective as thrusting weapons. A sword like Tizona is built to chop like a broadsword, but also thrust like a rapier.

Speaking of which, allow me to take a moment to rant about one of my big pet peeves in the Chinese martial arts – the mistranslation of dao as “broadsword.” The term “broadsword” arises somewhat as a distinction to separate it from the slimmer-bladed rapier. A European broadsword is straight and double-edged, more like a Chinese jian. It’s an unfortunate mistranslation because by now it has stuck so deep in our backs that it is nearly impossible to correct, and it distances us from the general verbiage used in the study of ancient arms. But I digress. Back to Tizona.

The Spanish School of Sword and Toledo

As I mentioned in my previous article, I formerly worked at The Armoury as a swordmaker. We actually made a sword that we called El Cid, but it looked nothing like Tizona. It was closer to the type of swords used in the 11th century. The nearest piece to Tizona was a sword we called Medieval Valencia because it had a curved guard with finger rings (actually I only mention that because I designed the original model from which that piece was cast, complete with the little skull adornment because I was really into skulls at that time). Don’t ask me about those sword names. I didn’t name those swords and I don’t know who did. But I will claim those illustrations because I drew them by hand. That was before computer illustration programs were readily available to the general public and the Armoury printed its catalog xerographically. Talk about old skool, but keep in mind, we made swords for a living.

Now, it is important to keep in mind the context of rapier, the ancestor of modern Olympic fencing. This sort of swordplay was predominantly for dueling – one-on-one matches of honor, not for the battlefield. Four centuries ago, the same criticisms that some traditionalists direct at MMA for being too limited to take on multiple opponents in real world terrain were leveled at rapier. Baltimore Knife & Sword’s expert craftsman Ilya Alekseyev, who also stars in MAN AT ARMS: ART OF WAR, elaborates. “I’m also well-versed in German and Italian rapier. German more so than Italian because Italians are too pompous and don’t know anything, like Joachim Meyer says. In fact it is in one of his manuals. He reluctantly includes the rapier in the combat manual saying, ‘This is a new weapon from Italy. They are very pompous and don’t know anything about swords, but since you will encounter it, this is how you use it.’” Joachim Meyer was a renowned 16th century German fencing master and author of several significant fencing treatises. In medieval and renaissance fencing, nations feuded about who had the superior style just like Chinese clans did with Kung Fu.

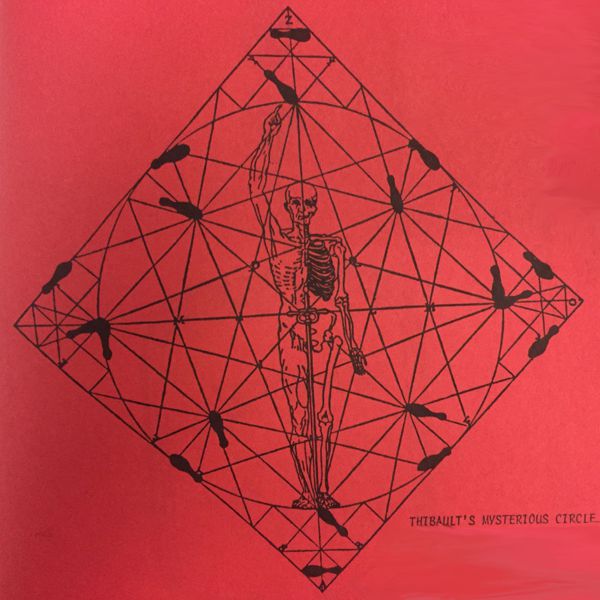

Within those feuds, the Spanish school is fascinating. Known as La Verdadera Destreza (The True Art or Skill), it dominated Europe for the 17th century and then fell into decline, overshadowed by the French and Italian schools. Now it is almost completely extinct in modern competition. However, a magnificent Spanish rapier manual survived, Academie de l’Espée, authored by Girard Thibault and published in 1628. The shortest distance between two points is a straight line, so when it comes to dueling with sword, fencing was very linear. Even today, it is fenced on a strip, a long narrow field of play. In contrast, Spanish sword was circular. It’s somewhat parallel to the dichotomy in the Chinese internal styles – the linearity of Xingyi versus circularity of Bagua. And just as those two styles became deeply connected with Daoist cosmology, the Spanish school of fencing was highly mathematical and geometric and, by some accounts, even astrological. Academie de l’Espée is illustrated with lavish engraved plates, and the centerpiece was known as Thibault’s Mysterious Circle, a marvelous example of European Renaissance art in the anatomical tradition of Leonardo da Vinci. Along with sculpting skull-adorned sword guards and illustrating the fencing catalog by hand, I also copied Thibault’s Mysterious Circle for a silkscreened T-shirt that The Armoury carried. It gave me the opportunity to try to decode those lines of attack, as well as to enlarge the figure’s penis, because the original image was inadequate in the opinion of the rest of The Armoury’s staff.

But I digress again. Back to Tizona and why it is arguably the most reproduced sword in the world. Tizona is one of the most famous swords of Spain, like Excalibur to the English. Spain is also home to one of the greatest swordmaking cities in the world – Toledo. Toledo Steel was historically one of the hardest, ideal for swordmaking. Toledo has been renowned for their metalworking since 500 BCE and held a reputation as one of the world’s greatest swordmaking capitals until the 20th century. In recent years, Toledo has continued to make swords along with jewelry and other metalworking objets du arte. However, given that swordplay is obsolete nowadays, just like most of the world’s ancient sword forges, the bulk of modern-made Toledo swords are for tourists. They are strictly decorative, not at all combat-worthy. For centuries, swordsmen venerated Toledo Steel. Today collectors disdain what they call “Toledo wall-hangers” – pretty swords but they can’t cut or thrust, made cheaply to sell to tourists, kind of like Modern Wushu weapons but just for display.

In late 2013, I made a pilgrimage to Toledo, Spain. It’s a wonderful place, full of old world charm and beauty, and I regret not spending more time there. The historical walled city, surrounded by a natural river moat, was full of countless sword shops – espadarias – with rack upon rack of swords and knifes. I was in sword shop heaven, like what the market of Valhalla must be. And I was delighted to find that they weren’t all wall-hangers. Nestled deep in those shops were caches of beautiful genuine swords, both modern replicas and a few antiques, sharp, tempered and ready to cut.

I had the honor of visiting Mariano Zamorano Espadas Toledanas. Master swordmaker Mariano Zamorano’s workshop has been in Toledo for 150 years and run by four generations of his family. He is one of the last real swordmakers in Toledo, declared of “Special Artisan Interest” by the Regional Government of Castilla-La Mancha. Master Zamorano was kind enough to give me a personal tour of his shop, even let me shoot some photos where photos aren’t permitted. I think he recognized a kindred spirit, even with my broken Spanish. His shop produces all kinds of swords now. They even make a dao, of forged carbon steel no less. But they don’t call it a “broadsword.” They call it a “curved Chinese sword.” And of course they make four Cid Swords, two versions of Tizona (one has a cast brass guard, the other is hand-made from iron), along with two versions of El Cid’s other legendary sword, Colada.

The Lunge

I had no idea that I was going to test Tizona. Marko Zaror was the designated stuntman for most of the MAN AT ARMS: ART OF WAR episodes with me. I’ve been a huge fan of Marko’s films for over a decade, back to his first films Kiltro (2006) and Mirageman (2007). I was so excited to learn he was in the cast and delighted to work with him. I told my wife that he was going to be my stunt double because our body types were so similar. She laughed. Anyway, the showrunners said I might be called upon to test a few weapons, so I did do some preparation.

I knew what weapons were in play, so for the first episode, Weapons of Kung Fu, I brushed up on some of my long dormant Bak Sil Lum forms. I never learned the Wind Fire Blades or the Ji, but knew I could fake Wind Fire Blades with the Tiger Hooks and the Ji with the Kwan Dao. I sought the coaching of my Bak Sil Lum elder brother, Master Ted Mancuso, who has an almost photographic memory when it comes to forms. Both forms came back to me pretty well and I did get to demonstrate the Wind Fire Blades. Let me tell you – it’s a whole different ballgame when the blades are razor sharp and there’s a huge film crew watching you.

I hadn’t done any cutting in years either. For that, I reconnected with another old senior classmate, Dov Nadel Sensei. He generously coached my rusty skills back with a day of slicing bamboo and pool noodles. I felt relatively confident as I walked onto the set of MAN AT ARMS: ART OF WAR. It reminded me of that eager anticipation back in the days when I used to compete.

However, when I was asked to test Tizona, it caught me off guard. The point (and yes, I’m making fencing puns here) of the Tizona test was to show it was a thrusting weapon, so I was to test it by stabbing a testing dummy in partial armor. It required my fencing skills. Fencing? Srsly? That was the one martial style that I didn’t brush up on beforehand. The last time I remember fencing was in the window of a gay warehouse party in San Francisco’s South of Market district. And that, like being double-certified as a Provost, is a whole other tale. (Don’t judge me. It was a paid gig. You got to get work wherever you can to make a living as a swordsman nowadays. My fencing years were weird. I blame the fencing knickers.)

Fortunately, I can still lunge. My fencing coaches made sure of that. Under Maestro Gaugler and the late Maestro Michael D’Asaro, the SJSU fencing team coach, I did tens of thousands of lunges. Hundreds of thousands perhaps. So many lunges. Unfortunately, there wasn’t too much I could do to make a lunge look that spectacular. It’s a simple move, like a straight punch. Marko offered me some advice off camera on how to add drama. I did what I could. What’s more, I was instructed to aim for a blood pack in the dummy’s skull but due to an oversight, there wasn’t one there. I hit the blood packs in the chest cavity, but a thrust isn’t quite as spectacular as a cut unless the blood packs are under pressure to simulate an arterial spray, just like in the movies. Hopefully the film crew shot it in such a way that it was more dramatic. As it turns out, it’s much harder to stab a test dummy than you might think. Whether it makes the final cut or not, well, I won’t know until the episode airs. If not, no great loss. At least I got a good story out of it.

Regardless, working on MAN AT ARMS: ART OF WAR was a lot of fun. I hope you’ll support our show and that we get renewed for a second season. I ride with El Rey.

Until next time, stay sharp!

Written by Gene Ching for KUNGFUMAGAZINE.COM

COPYRIGHT KUNGFUMAGAZINE.COM, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

All other uses contact us at gene@kungfumagazine.com

Subscribe to Kung Fu Tai Chi Magazine today!