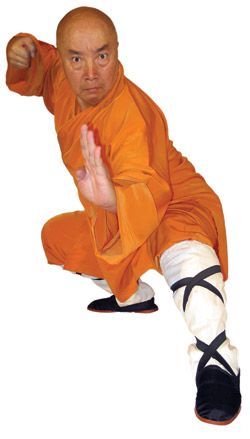

Americans best recognize Grandmaster Hai Yu as the big monk from the Shaolin Temple film series. Three films were shot on location at Shaolin Temple in the early eighties: Shaolin Temple (1982), Kids from Shaolin (1983) and Martial Arts of Shaolin (1986), aka North and South Shaolin. Each starred Jet Li in top billing with Yu in a supporting role. The Shaolin films were only connected by location and marketing, not by storyline, so Jet and Yu played different characters in each film. But Yu’s role was always the same. He portrayed Jet’s master, a tough yet tenderhearted Shaolin monk.

Americans best recognize Grandmaster Hai Yu as the big monk from the Shaolin Temple film series. Three films were shot on location at Shaolin Temple in the early eighties: Shaolin Temple (1982), Kids from Shaolin (1983) and Martial Arts of Shaolin (1986), aka North and South Shaolin. Each starred Jet Li in top billing with Yu in a supporting role. The Shaolin films were only connected by location and marketing, not by storyline, so Jet and Yu played different characters in each film. But Yu’s role was always the same. He portrayed Jet’s master, a tough yet tenderhearted Shaolin monk.

Seasoned fans and martial artists know Grandmaster Yu is much more. For nearly half a century, Yu has played a pivotal role in the advancement of Chinese martial arts and is one of its greatest innovators. A highly respected master of traditional mantis style, Yu created his own mantis form which is widely practiced by both traditionalists and modern wushu players all around the world. He was a founding father of modern wushu and served as one of the cultural ambassadors during the historic 1974 wushu to the White House tour. He and Jet Li, together even then, were among the first citizens of communist China to ever step foot in America, demonstrating right on the White House lawn for President Nixon. Known for his integrity, Yu became disenchanted by the politics of the martial world and left for nearly a decade. He returned in the new millennium armed with a new form of his own invention. But this one, he isn’t really sharing.

A Christian in a Den of Mantises

Hai Yu was born in Yantai, a northern port of Shandong province. He was one of five children, but his elder brother and sister both died young due to poor health and unsanitary conditions. With only younger sisters left, Yu inherited the most precious position in a Chinese family as the eldest male. But just like his deceased brother, he was a sickly child. His father was a worker for the electric company and a devout Christian. In fact, Hai Yu’s given name was Wu Tiantang ( tiantang means “heaven” and is a common name among Chinese Christians). Fearing for his bloodline, Yu’s father sent him to a Christian friend named Lin Jingshan (), a master of Seven Star Praying Mantis (qixing tanglong ), in hopes of fortifying his son’s constitution. Yu was around nine years old then.

Shandong is the birthplace of mantis. All of the pioneers in Seven Star, Plum Flower (meihua ) and Six Harmony (liuhe ) mantis came from this northeastern province, where wild mantises thrive everywhere. Near to Yu’s hometown lies Laiyang, considered the birthplace of Seven Star Mantis. In addition to Seven Star, Yu also studied Plum Flower Mantis from his aunt’s husband and exchanged skills with many other local practitioners.

In April of 1959, the first Yantai competition was held. By then, Yu had over half a decade of practice under his belt. His teacher encouraged him to compete, despite Yu’s own misgivings. Much to Yu’s surprise, he won a slot as the Yantai representative for the Shandong Province championships. A few months later, he did well there too, securing a position on the Shandong Province team for China’s historic 1st Athletic Games. There he earned second grade (like the ancient Confucian examination system, competitors weren’t awarded lone first, second and third prizes; instead they were classified by first, second and third grade). Yu was quite pleased with second best, especially since he lacked the guts to compete until his teacher pushed him.

Yu went professional by his mid teens. While in middle school, he planned on following his father’s footsteps as a common laborer. But now he was earning a decent salary of five dollars a month as a martial artist. That might not seem like much today, but back then it was enough for Yu to send half of it home every other month to help support his family. By his second year, his skills improved enough to garner higher scores in tournaments. His salary was increased to a whopping $39.50 a month.

The ’60s Revolution

From 1960 to 1962, China underwent a devastating period known as the Three Hard Years. Fallout from Mao’s Great Leap Forward, coupled with a nationwide famine, resulted in some thirty million people starving to death. During that period, martial arts came to a standstill. But as things got better, China took its first steps towards modern wushu. New compulsories introduced aerial moves like barrel rolls and twists. Yu has a stocky, barrel-chested frame, not the best body type for high jumps. He knew he couldn’t jump that high. Not wanting to disappoint his parents or teacher, he redoubled his efforts, but his plan backfired.

“I tried to train harder than anyone else,” confesses Yu in Mandarin. “Everyone trained hard in the day. So just before I went to sleep, I would drink a lot of water. Then I would have to get up in the middle of the night to pee. I’d get up, pee, and then sneak another hour of training in by myself.” Yu chuckles at his childhood strategy now. “That was very stupid. It could hurt your health.”

Yu ended up injuring his back attempting aerials. “In the beginning, the coaches didn’t know how to train back flips or barrel rolls,” reflects Yu. “There was no scientific method. That’s how I got hurt.” It was a heavy blow to his confidence. He joined some half dozen other kids on the injured list. They didn’t get to train with the others. Instead, they got herbal treatments and massage. He went to his coach and confessed his doubts. Maybe he just wasn’t fit for this. His coach retorted, “If others can be heroes in the sky, why can’t you be a good man on the ground?” That comment opened his eyes, literally. Yu began to focus on his stance work and his eyes.

Yu continued to train at night, but now instead of worrying about his bladder, he focused on his stare and his presence, a quality known as jing qi shen (essence, vital force, spirit ). In the dark, he would imagine a dire wolf was right behind him. Then he would whip around to face that wolf, bringing all his intensity into his eyes. Anytime he had the chance, he would visualize being attacked and react. Once there was a guy behind him, but Yu didn’t know it. Yu turned with such intensity that the person freaked out and ran.

Yu continued to train by himself, regaining his strength through jogging and mountain climbing. In 1963, another national competition was held. Yu wasn’t going to enter, but in the last three months prior to the competition, his coach saw enough improvement to reinstate him on the team. Yu lacked confidence because of his injury and his unfamiliarity with the new routines. He competed in staff, sword and mantis. Nervousness made him slip and touch his hands to the floor in staff, but the judges were lenient with the penalty and he still placed third. In sword and mantis, he placed first. Yu brought home the highest scores for the entire Shandong team.

In 1965, another National Games was held, but it was only exhibition. Shandong placed above all others in total scores, garnering the nickname “big brother” team because they were so good. The following year, Yu became the team leader and coach. He was the youngest team coach in China at the time.

In an often overlooked period of wushu history, there was a movement to abandon traditional weapons like spear and sword, and replace them with tools of the modern laborer. The sickle and hammer were symbols of Communism and perfect candidates. Other common tools like butcher knives and pot lids also became weapons. These were far more “street” practical since they could be found anywhere in China. Hai Yu was one of the principle masters behind the creation these new forms. Eventually, the movement fizzled, engulfed by the fires of the Cultural Revolution. Those weapons, despite their practicality, are seldom seen in practice anymore.

Out of the Ashes, a Mantis Is Born

Hai Yu’s most famous contribution today is his mantis form. It was showcased in Shaolin Temple 3, and became a mainstay at the real Shaolin Temple, setting the standard for mantis among modern wushu players. “Traditional mantis was only twenty or thirty seconds long – too short for competition,” recounts Yu. “It looks bad to put two forms together. They don’t coordinate. So I asked my coach. He said, ‘Look to our ancestors to make it longer.’ This was during the Cultural Revolution. There wasn’t much work.”

It is a commonly reported fact that martial arts were banned during the Cultural Revolution. But just like drug use in America today or liquor during the prohibition, making something illegal seldom stops it. It just went underground. As long as people kill each other, authentic martial arts will survive. It will always be kept “real” by both perpetrators of violence and defenders of the weak.

“I went to the mountains with a few students,” continues Yu. “We caught mantises and put them in a big mosquito net. At one point, we had as many as a hundred mantises in there. I used a straw to play with them and watch their movements. When I touched them, they blocked or attacked. From all those movements, I made all sorts of combinations and made my form longer.”

Yu took his creation to the competition floor where it was well received. He asked other masters for opinions and made modifications based on their sagely advice. “These bad parts weren’t bad because the mantis was bad. They were bad because I couldn’t interpret the mantis movements properly. So I went back, worked on them some more, and then put them back in. By that time, the masters who criticized the movements before saw them again and approved. The form is not Seven Star or Plum Flower. It’s unique.”

During the seventies, Yu’s notoriety as a leading master increased. He was the eldest performer on that famous White House tour and traveled extensively on other martial ambassador tours. Like Jet Li, Yu began his film career with the groundbreaking film, Shaolin Temple, catapulting Yu into China’s public eye like few martial artists ever achieve. China officially recognized its martial celebrities. Three international martial arts stars were predictable: Jackie Chan, Bruce Lee and Jet Li. Inside China, the three national stars were declared as Yu Chenghui, Ji Chunhua (known to most Americans as ‘Bald Eagle’) and Hai Yu. Meanwhile, modern wushu was growing at an alarming rate, and with it grew a bureaucracy of petty tyrants.

Walking Out on the Wushu World

Yu dropped out of the martial arts scene for almost a decade. Following the Cultural Revolution and its successive renovations, he found himself at odds with the way martial arts were going, especially the niggling politics. After completing Shaolin Temple 3, Yu was invited by the Taiwan-based movie company to travel and promote it. He needed to submit a visa application, a task that he obediently deferred to his superior. However, his superior denied knowledge of him. Yu shakes his head at the memory. “The promoter came to me and said, ‘I can make things smooth. I don’t think he doesn’t know you. He didn’t give me a proper answer. I think he just wants you to bow to him. If you bring him two bottles of wine and give him face, I think he’ll approve.’ I couldn’t do that. I couldn’t even bring myself to give him the cheapest bottles. We say ‘bow your waist for a five scoops of rice’ (wu dou mi zhe yao ). This means if you work for someone, you must bow to them. But I was already semi-retired and this wasn’t a matter of life and death. I had already traveled a lot. I went to Czechoslovakia and Russia. I went to Burma with Zhou Enlai. I went to America in the ’70s. When I traveled, I didn’t get extra pay. Maybe I ate a few good meals, but I didn’t really care. I wasn’t going to bow. The roof over my head was made of mud and straw, not concrete, so it wasn’t going to hurt me if it fell.” Yu never gave that official face, so he didn’t get to go.

In 1990, Yu went to Shanghai for a three-day open competition. There, another coach pulled him aside and said, “Nowadays, I don’t know how to give scores.” Yu was shocked. How could he say that? Then, when the results came in, Yu saw that many of the talented competitors who should have placed in the top three didn’t even make the top ten. The winners bribed their way to better scores. Yu was so disgusted that he walked out. He stopped reporting to his superiors and steered clear of political games. He hasn’t stepped into an open tournament since.

When China instigated the duan system to rank masters, he didn’t bother to submit an application at first. He was convinced that he should apply for the second application period, so he submitted for 8th duan. He was only given 7th duan. Many of the 7th duan masters were his students. Yu’s disregard for martial politics cost him, but in the end he could care less. “I prefer to have zero duan,” says Yu now with a smile.

Returning to the Source

Just like Bodhidharma, Yu lived like a martial hermit for nine years. During that time, he studied Buddhism and Yoga, and took a keen interest in the Six Harmonies. Beyond being the third major school of mantis, liuhe bafa (six harmonies, eight methods ) is a progenitor of Chinese martial arts. All the elder styles have had plenty of time to evolve, so with liuhe bafa, there are many different versions. Some are even contradictory. Being Christian, Yu didn’t believe in criticizing others. This was reinforced by his teacher, also a Christian, especially when looking at other styles. “My teacher had iron finger skills,” remembers Yu. “If he ever caught any of his students speaking poorly of someone else’s form, he’d poke us and we’d be badly bruised.” With that perspective, Yu learned to just observe, absorb what was useful, and not be attached to lineage or any traditional framework. Instead, he took what worked and forged his own practice.

Yu studied the different interpretations of Six Harmonies intensively, taking the best of each, and combined it with some elements of Chen taiji. In the end, he came up with something new that wasn’t really liuhe bafa anymore. He calls it yuhui daofa (universal rule method ). “Some forms were created during the revolution period,” elaborates Yu. “Now everything made then is considered bad. Yuhui daofa means it is everlasting. It’s a true method.” Yu doesn’t really teach or demonstrate this new form. It’s really just for his personal private practice.

Today, Grandmaster Yu is still promoting martial arts. He is a visiting head coach at several martial schools, one in Guangdong, one in Beijing, another in Zhejiang. But after his nine-year respite, he now feels he’s just a normal martial arts teacher. “Now some call me the ‘King of Mantis,’ but I never claim that,” says Yu emphatically. “People just wanted to say that. I’m just a martial arts master and teacher.” Yu doesn’t want to be a celebrity like Jet Li, nor some lofty, unapproachable master. “I’m not afraid to go out in public. I can still ride my bicycle to buy vegetables at the market. If you say ‘hi,’ I’m happy to talk to you.”