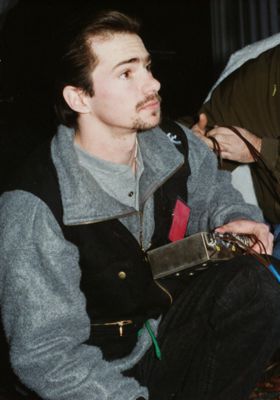

Mark Grove explains how he has adapted his own Ninjutsu to the film industry, before presenting the first section of a choreographed fight for aspiring action actors to learn from.

In prior installments of this column we have talked about the entertainment industry, preparing materials to promote yourself, and even the fundamentals of how to adapt your martial arts to the big screen. But before I go on, I feel that I must share with you my own inspiration for entering the film business.

I began training in the Japanese martial arts of Ninjutsu and Kenjutsu in 1972 and I opened my first Dojo in 1983 at the age of 17. Young and full of energy, my school prospered. The 80’s were especially good for my art. The world seemed obsessed with anything Ninja related and it dominated magazines, movies, television, comic books, video games and toys. This was very positive for enrollment. But as the years went on I realized that there was something missing. I had no outlet for my skills other than teaching. To be clear, there are no sport competitions for practitioners of this art and unless you work in the military or law enforcement, there are very few practical uses for Ninja skills in the modern world. It was this realization that made me wonder what an occidental Ninja far removed from Japan’s feudal era actually does with his skills. I know I’ve opened myself to rebuttal here. I am almost certain that many would argue that regardless of style, martial arts principles are VERY applicable in everyday life. I will not argue that point.

I understand the value or martial training in terms of confidence, discipline, self-defense, mental focus, spiritual refinement, and so on, but I am specifically referring to the application of the learned skills. I really wanted to utilize my Ninja training. Unarmed combat, acrobatics, classical swordsmanship, exotic weaponry, explosives, climbing, and the dozens of other skills that together make up the in-depth art of Ninjutsu. But what field would maximize their value?

Entertainment. It was a simple and obvious choice for me. Then another realization hit me. I was not the first to feel as though my martial skills had no place in the modern world. In all things there is a first, and I would once again find inspiration from the very country from which my martial art originated. Japan.

DEATH OF A WARRIOR CASTE

It happened during the Meiji restoration in Japan (1877-1912), where the Samurai class was abolished and thousands of warriors who had served their lords in battle over many centuries were forced to hang up their swords. Ironically, it was also during this time that moving pictures began to take shape under such visionaries as Thomas Edison (Kinetoscope) and Louis Lumiere (Cinematographe). The ability to record visual images presented a new way to capture and preserve knowledge.

THE FIRST CHAMBARA FILM

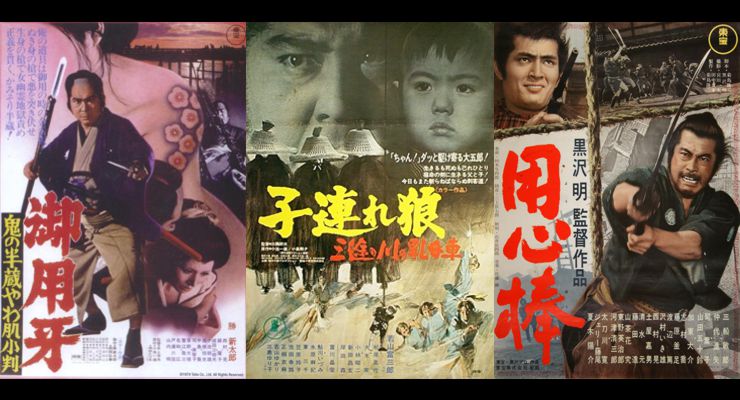

Japan’s action films dealing with the Feudal era are known as Chambara, which is slang for Japanese swordplay or swashbuckler films. These films are generally set in 15th- to 19th-century Japan. The first Chambara film titled “The Fight at Honno Temple” was released in 1908 and its director, Makino Shozo, became known as the father of Japanese cinema. This film utilized the fighting techniques found in traditional Kabuki theatre productions, but because of the films popularity, many renowned sword masters became the primary source of inspiration for developing the techniques that would be used many decades later to create the Samurai and Ninja epics of the 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s.

REAL TECHNIQUE

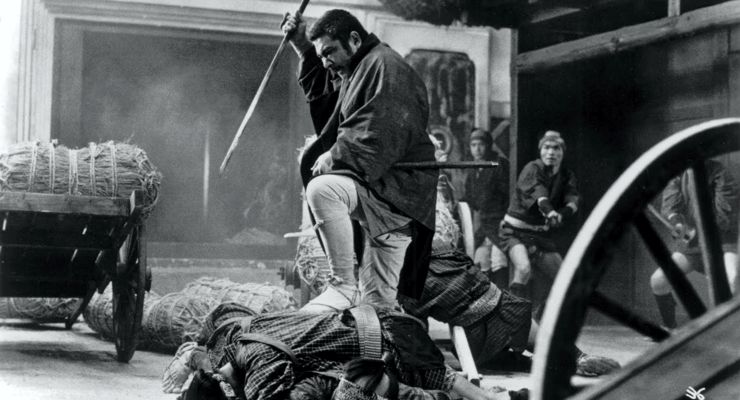

Having the wisdom and skill of classically trained swordsmen brought a new sense of “Realism” to these films because the characters actually used historically proven fighting techniques that had been adapted to film. The significance of the Chambara film genre in world cinema is enormous. Stoic heroes fighting against unbeatable odds, honor and loyalty tested, and betrayal at every turn.

THE EASTERN WESTERN

Inspired by the Westerns of Hollywood, Japanese director Akira Kurosawa made a few of the most memorable Chambara films. Among Kurosawa’s best-known swordfight films are “Seven Samurai” (1954) was later remade in America and titled “The Magnificent Seven.” The Hidden Fortress (1957) is acknowledged as an inspiration for “Star Wars,” and “Yojimbo” (1961) was remade as “Fistful Of Dollars.” Directors like Kurosawa brought dirty realism to the Chambara genre, evoking a world of immorality, violence and sudden death.

I understand the value of martial training in terms of confidence, discipline, self-defence, mental focus, spiritual refinement and so on… but, I am specifically referring tothe application of the learned skills. I really wanted to utilise my ninja training. Unarmed combat, acrobatics, classical swordsmanship, exotic weaponry, explosives, climbing and the dozens of other skills that together make up the in-depth art of ninjutsu. But, what field could maximize their value? Entertainment… it was a simple and obvious choice for me. Then, another realisation hit me – I was not the first to feel as though my martial skills had no place in the modern world. In all things there is a first and I would once again find inspiration from the very country from which my martial art originated – japan.

Death of a warrior caste it happened during the Meiji restoration in Japan (1877-1912), where the samurai class was abolished and thousands of warriors who had served their lords in battle over many centuries were forced to hang up their swords. Ironically, it was also during this time that moving pictures began to take shape under such visionaries as Thomas.

POWERFUL SERIES

Chambara was also popular in a variety of film series including; “Zatoichi” (1962-72), “Shinobi No Mono” (1962-66), “Hanzo The Blade” (1972-74), “Lady Snowblood” (1973-74), and based on the epic Manga comics by Kazuo Koike and Goseke Kojima the amazing “Lone Wolf And Cub” series (1972-74).

TRADITION RECORDED

Just like the ancient scrolls passed down from teacher to student, Chambara films serve as visual representation of classical arts. So in the late 1980’s I too began my personal quest to adapt the skills of my tradition just as those brave Samurai did over a century ago. A way to preserve an art I have dedicated my life to. But creating a Chambara system was not an easy task. The desire doesn’t magically bring the craft to life. I had to develop a new way of thinking. A new way of applying every aspect of my art so that it would adapt flawlessly to film. I knew that in order to deliver the best possible action I would have to acquire information. No problem… that’s what a Ninja does best.

SEEKING KNOWLEDGE

I had to find great mentors. I sought the assistance of talented stunt coordinators, special effects technicians, acting coaches, and other film professionals. These people were Black Belts in their individual fields and I knew their insights would be invaluable. But I also knew they would not come to me. Like martial artists, some of these people would have special ways of doing things that were closely guarded secrets. I would have to seek them out and somehow prove I was worthy of their attention.

STUNT TRAINING

Within the first few months of my quest, I found a stunt coordinator (Lars Lundgren) willing to take me under his wing. It was from him that I would discover that with a good working knowledge of camera technique my Ninja unarmed and weaponry skills were perfectly suited for film. My ability with acrobatics and falls were enhanced so I could fall from much grander heights, I could be thrown from fast moving vehicles, and I learned perform intricate aerial maneuvers through the use of wires. He would also teach me skills that made me face many new challenges, such as setting myself on fire, being dragged behind moving vehicles, and the use of modern firearms.

SPECIAL EFFECTS TRAINING

I studied diligently and acquired my high explosives license so I could do everything from bullet hits to full-on pyrotechnic destruction.

You wouldn’t think that Ninja skills would translate to the special effects industry, but Ninjutsu is often referred to as the art of “illusion”. So what better place to put that concept to use. I began my quest by utilizing the Ninja art of “Hensojutsu” or “The way of disguise”. The Ninja had to be adept at transforming themselves physically so they could disappear in plain sight. I studied modern applications of this concept by creating and/or applying prosthetic make up. I also took the Ninja art of “Kayakujutsu” or “Fire an explosives skills” to the next level. I studied diligently and acquired my high explosives license so I could do everything from bullet hits to full on pyrotechnic destruction. I continued down this path and gained knowledge with chemical effects, weather effects, firearms handling, and pneumatic effects.

PERFORMANCE TRAINING

My movement and acting coaches were possibly my favorite. Beyond the disguise skills that made the Ninja “look” the part, they also had to be able to “act” the part. To a Ninja this is the skill known as “Hengenkashijutsu” or “The immersion into the illusion”. It is through this art that the Ninja truly learns to emulate the persona they are attempting to portray. Long hours of practice in assuming the personal traits of the character and any other special skills the role might require. A Ninja can be heroic, vulnerable, stoic, benevolent, or whatever emotion will help accomplish the mission…and in this case, the mission is creating a believable character.

A NEW BATTLEFIELD

Thus, in true Ninja fashion, I found a way to maintain my art in an industry that some would call a battlefield in its own right. After over two decades working in the film business I have used my skills as an actor, stuntman, fight choreographer, stunt coordinator, special effects supervisor, make up artist, writer, producer, and director… and all without the need to use my Ninja arts violently on another human. No one had to lose in order for me to win. It has been the perfect scenario except for one element. Many who meet and work with me regard me as a “film” person rather than a “martial artist”. What they don’t realize is that at my core I am and always will be a shadow warrior. I simply choose to employ my craft in a different arena.

A MISSION REINVISIONED

Until recently I didn’t realize that there was another step I must take if I am truly going to complete my mission. Yes, I did adapt my art and I have employed it in the industry. But I am reminded of something I was told long ago. “If a wealthy man dies hoarding his riches, then he lived poorly”. The meaning of this statement is all too clear. All that is not given is lost. Thus my mission must evolve. I now have two new objectives. First, I have a strong desire to do everything in my power to reinvigorate the martial arts genre in projects that I develop and create. I want to honor the arts. No matter the country of origin, there are many martial arts that have rich histories and amazing fighting skills that could be captured on film for the world to experience. Secondly, I am focused inspiring and teaching others to follow the same path with their arts that I did. It is possible. And the lessons start here.

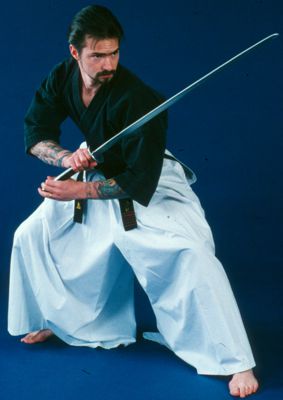

WAY OF THE SWORD

As an example of Chambara technique, we absolutely must begin with the sword. The classic Japanese art of Kenjutsu (sword fencing skills) is extremely complex. It takes years to learn the primary techniques and even longer to refine them. Unfortunately if we start at the basics it would not make for an interesting demonstration of Chambara in action. So we have to jump into the thick of it and do a multi-move choreographed fight.

The first choreography will consist of one 10 move sequence that when put together with future sets will form a complete fight. Choreography is broken down in this fashion so that small pieces of the fight are shot one at a time to allow for continuity and effective camera movement.

FIGHT SEQUENCE ONE

The Swordsman begin facing one another. They draw their swords and extend them forward into a guard position. Next both Swordsman circle to their right as they assume different postures to show personality. Swordsman 1 holds the sword vertically to her right side. Swordsman 2 holds the sword diagonally across his body. Swordsman 1 executes a low side cut to the left lower leg of Swordsman 2. Swordsman 2 rotates his blade in a circular fashion to block the attack. Swordsman 1 immediately spins around and executes a high side cut. Swordsman 2 raises his weapon up vertically to his right side with the tip pointed down to form a shield. From the block, Swordsman 2 executes a downward attack to the head of Swordsman 1. Swordsman 1 spins to the left and uses her sword to deflect the attack. Swordsman 1 then executes a downward feinting attack to make swordsman 2 raise his sword in defense. At the last minute, Swordsman 1 pulls the attack into a chambered position in preparation for a thrust. Swordsman 1 thrusts as Swordsman 2 uses his blade to parry and redirect the attack into a circular control. Swordsman 2 then executes a high side cut as Swordsman 1 pulls her sword in to deflect the attack. Swordsman 1 then uses her sword as a lever to manipulate the sword of Swordsman 2 over her body and into a trap against the ground. Swordsman 1 then uses her sword guard to slam Swordsman 2 in the face – Lead in to sequence two.

Next month in Get Your Career In Action: Reel Ninja Part two, we will add two more sequences to the fight and provide a web link so readers can view the fight in its entirety as it would actually be filmed. Until next time.

Learn more about Mark Steven Grove’s Rocky Mountain Stunts on the Martial Arts & Action Entertainment Directory by clicking on the image on the left. Rocky Mountain Stunts provides expert stunt coordinators and fight choreographers, stunt performers and set construction, prop creation, prosthetic makeup, and environmental effects.