In part two of his Burmese Odyssey interview, Vincent Giordano discusses his dealings with the earlier oppressive and xenophobic military junta that endorsed heavy censorship on all media within the country. Vincent’s ability to move through most of the country during this time and continue filming over a decade is a testament to his resolve and tactical strategies.

What were some of the first things you did once you got to Myanmar, to get inside the sport?

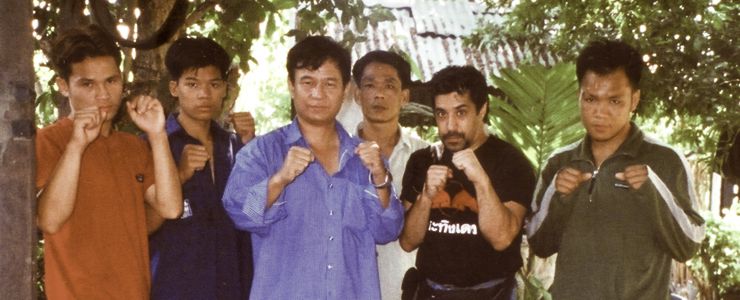

It started before then, being up in the North of Thailand during Songkran, and meeting some of the Burmese Lethwei fighters from the Myawaddy division. The fighters told me about upcoming fight cards in Myanmar, sharing information about trainers in Yangon and the Kayin State. The fighters, due to a lack of tournaments, kept on the move traveling from place to place looking for cards to fight on.

Later when I showed up at a tournament in Yangon, many of the fighters I met earlier, greeted me warmly and introduced me to others on the circuit.

I would check with them about filming, and they would help clear it for me. I am heavily indebted to these fighters because they opened the first doors for me. It was up to me from then on to continue to maintain relationships that would help with my work.

What was your actual approach in capturing the live events and practice sessions?

You can see most of the time people who film martial arts really try for a polished performance, as opposed to a sometimes raw presentation of the art or fighting sport. I am less interested in physical education rigor or theatrical performance in my documentary work. I want it to be honest and from the heart, rather than polished and rehearsed for the camera. If it’s polished and good, then so be it. But I rather get it with the live energy percolating through the movement. Just letting it be, as it is.

The camera and taking notes, doing interviews and putting together the system or training plans comes next. I don’t pull out a camera until I feel the time is right. It becomes a natural extension of who I am, in relation to them. If you do it correctly, they accept the camera presence as they accept me.

This process took a long time to develop and cultivate. Many times, I worked with bands that didn’t want to be filmed or disliked the camera. But if I got them to like me and warm up to the camera, I could create an environment and shooting style that would work for both of us. So much so, that those who even hated being filmed would say “You missed what happened yesterday, where were you” which always made me laugh. They eventually became comfortable enough with the process, that they wanted to be filmed all the time.

Still the problem exists in how do you move around and freely film, while being heavily monitored within the country?

I knew I’d be monitored within Myanmar but how heavily or persistently, and what would happen as a result was a complete mystery. Would they confiscate my material, eject me from the country or would I just get lectured about how to behave as others had experienced before me? My experience ultimately was a little different. It’s quite odd thinking back to it.

I didn’t realize at first what was happening. People who I enjoyed being with where falling away. Refusing to return my calls or see me. It seemed everywhere I went, a shadow followed that crumbled the path I was walking on.

I didn’t realize at first what was happening. People who I enjoyed being with where falling away. Refusing to return my calls or see me. It seemed everywhere I went, a shadow followed that crumbled the path I was walking on.

I was later told in a small Yangon tea shop by my Burmese friend, what had happened. People were visited right after I left and had been interrogated about my presence. They were scared that if I came back, it could get worse for them. Some were threatened. I realized I needed to formulate a stronger game plan. In the other countries, I always worked with the military who were heavily involved in martial arts activities, and could open doors for me. I couldn’t do that here. Americans were despised by the military, especially those with cameras, filming and documenting things.

I decided to align myself with the remnants of the Olympic boxing team that was in tatters from extreme neglect and lack of high-level participation in global events. Things immediately started to move in the right direction when I did this.

I had to accept that I’d be monitored. I also had to be more vocal and honest about why I was there. After time and multiple visits, it became clear I was not there to start trouble. I didn’t write about the situations or mention anything then, as not to call attention to what I was doing, or involve others on the ground due to things I said. It’s one of the reasons the material stayed locked up for so long.

Where there any moments that you felt things got frightening or way out of hand?

Yes, there were many. This part would actually warrant a full interview, because just this topic alone, to explain and cover what transpired would take time. It’s Myanmar, and nothing is easy to explain. I take a lot of risks in my professional career, maybe too many. Any success thus far has been invariably linked to my willingness to take those risks. There were times when I had to take a second to think about how far I was willing to push things.

Remember, Lethwei is the smallest part of this journey. I did more work on Naban, Thaing and the spiritual and healing traditions than Lethwei. So it’s much more extensive and deeper than just the sports coverage.

One incident though that remains vivid happened in Mandalay. I previously had a close call when I got too excited seeing a chain gang working below me, and tried to grab some footage of the situation. An alarm went off. A parade of people came charging at me, but I darted away before they could get anywhere near me.

A month later, I went to visit some of the Burmese Pongyi or monks who trained with the Black Buffalo Thaing school. The monks trained at midnight away from the prying eyes of the military. I was invited to stay with them for a few days. When I got to the base of their temple, there was a tank blocking the entrance, with several armed and agitated soldiers pointing guns everywhere. A noisy, flat-bed truck whizzed by me, and I caught a glimpse of what looked like bodies piled up in the back. When I looked at the ground, there was a trail of blood seeping out the back of the truck.

My Burmese research assistant and I were trapped because we couldn’t turn around. I told him to tell it straight to the soldiers, that were going to visit our friends in the temple. This didn’t translate well because as a foreigner visiting a temple where there was evident trouble, meant I might have been there to document the incident, or get the monks message out. This event I later learned, was part of a protest by the monks during a visit by the United Nations. They wanted to show the UN officials, that the military was still secretly cracking down on them and executing monks at will. But the protest never got very far, because the military locked down the temples, killing those who had gotten out.

The young soldiers kept their guns on us. They said there was a curfew starting now for me. I was to report back to my hotel and stay there. On the way back, I decided I’d go to my room, throw my bags out the window and get out of there. I had already paid for my room, so I gave some money to a young kid to run the door key back.

We determined that the safest bet was to head north to Myitkyina in the Kachin state since there was no trouble there. We hired a car to drive us, but this was not the best choice. The person was a simple animistic who was raised in a very primitive culture, but he was the best driver who knew the route, driving it daily. He was fearful of a particular part of the jungle where a spirit supposedly comes out and calls to him. He said he speeds up to avoid it because it’s sure death if the spirit gets to him. I warned him not to speed up or do anything insane like that since I was in the front seat with all my camera gear and belongings.

Unfortunately, I fell asleep and the next thing I know my head cracks hard into the side window, waking me up to the sight that we are now airborne. For some reason, the car doesn’t overturn but lands back down on all four wheels. My head is struck again and my bags and cameras sail right out of my hands. I have whiplash. My neck becomes tighter and tighter. My camera is damaged. The lens has cracked off the body. It’s a total disaster. I only remember being body tackled by the other people in the car because it was the one moment I wanted to kill someone. So in fleeing from one horror, I was met with another. There are many more like that.

How does the sport of Lethwei survive through all these critical changes in the country?

Its survival rested with the rural communities who kept it alive through their annual festivals and holidays. Lethwei contests have been a part of those celebrations for centuries. I feel one must experience Lethwei at the festivals to gain a deeper understanding of the ancient roots and cultural resonance the sport has in the lives of those growing up outside of places like Yangon. At one time, Lethwei was a part of a rite of passage into manhood for many young men growing up in these rural communities. A boy could proudly display his strength and virility during these contests to his family and community, while earning money and gaining a reputation as a fighter.

In Yangon, as documented in Part 1 of Born Warriors, a small group of promoters, trainers and fighters, worked tirelessly to sponsor Lethwei tournaments in the major arenas. They were working hard to put on exciting events and promote the sport. But they were shackled by a lack of support and governmental control. The promoters had to work through a lot of red tape. A show could be canceled at the last minute due to the whims of the military. They could do this because any public gatherings had to be cleared, and would be called off if they felt there was any danger in holding the event.

When the country started opening up, many of the original promoters and trainers that were still actively involved in Lethwei, again tried to reinvigorate the sport. But this time there was a massive influx of outside business people who saw the sport more as a commodity. It was just an investment to them. Even greedy government agencies saw a way to get cut in on the proceedings. The money that came in from different sources went toward larger shows that began to raise the visibility of the sport in the major arenas in Yangon and Mandalay. Several of the bigger shows were televised live and shown as far away as Singapore. This saw the sport flourish.

The importance of Myanmar for the study of bare-knuckle fighting is that it has remained an ongoing tradition that survived, despite insurmountable odds against it. It maintains the ancient roots in the rural communities while pursuing modern ideas in the big arenas.

Born Warriors was shot over a long period of time. It must have been frustrating trying to hold it together for so long. Did you ever want to give up?

It’s not about giving up but seeing how you can get each project done. There’s a myriad of paths. Can what you have transition or morph into something else, or be part of another body of work? Or are you going to stick with it and grind it out? Documentaries don’t come together the same way as other projects. They seem to move you in the direction they need to go in. A person or event can suddenly become a catalyst for a renewed attack on a premise. Sometimes you still hit a dead end, despite your best efforts. One thing is that these type of projects take time to do. Born Warriors really died and needed to be resuscitated with a new approach. Some of the footage was damaged, while there were format and shooting changes from SD to HD. We had no money and no interest, so I just pushed ahead and tried to do what I could. It was very frustrating, but the challenge of it kept me going. It took years of work.

Where did you draw your inspiration?

The inspiration comes from the world and culture I am exploring, and the people themselves. I was very inspired by the work of Werner Herzog during this time. He has his own way of viewing the documentary film. His body of work is fearless, and he doesn’t shy away from the dangers of prolonged physical journeys. I had the rare privilege of meeting him early on in my career. Errol Morris, another great documentarian and a wonderful human being, allowed me to rent his edit room to finish a small narrative project I directed. He was very gracious with his time and allowed me to sit in and talk with him when he was free. One day when he was out, someone was pounding on the door. It was Werner Herzog. He, of course, in the absence of hunting down Errol, had to follow me around and interrogate me to see what I was working on. It lead to some fascinating conversations, especially when Errol returned to meet with him. It’s those moments that are invariably etched in my mind. They help you at just the right time in your life.

What I got most from Herzog beyond his obvious intelligence and filmmaking ability, was his fierce determination never to quit. It’s hard to give up. It’s not part of my nature. I put some much into everything I do. But sometimes a project can get the better of you, no matter how much you love it. I was lucky that this time, that I was able to see it through to the end. It wasn’t easy by any means. Regardless of what happens from here. I accomplished what I set out to do, and to me that’s all that counts.

For further information on Born Warriors:

For further information on The Vanishing Flame:

The Vanishing Flame on Facebook

© 2016, Guillermo Xegarra