In 1971 the American public knew little about the martial art known as hapkido. Then came the movie “Billy Jack” and an unforgettable performance by a then-unknown martial arts instructor, Bong Soo Han.

In 1971 the American public knew little about the martial art known as hapkido. Then came the movie “Billy Jack” and an unforgettable performance by a then-unknown martial arts instructor, Bong Soo Han.

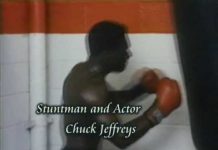

Standing nearly nose to nose with one of the movie’s villains, Han, a stunt double for Tom Laughlin, the movie’s star, delivers a quick kick to the man’s jaw, flooring him. Billy Jack received mixed reviews from critics, but such scenes captured the imagination of the moviegoing public and sent some out seeking to learn the art.

Those early students found Han at his dojang, or studio, in Santa Monica, as did thousands of others. For the rest of his life, he taught and promoted the martial art through his International Hapkido Federation, earning recognition as the father of hapkido in the Western world.

Bong Soo Han died Monday at his home in Santa Monica from complications of cancer, said Jon Davis, a spokesman for the family. He was 73.

“He was, for me, the quintessential martial artist,” said Joe Hyams, an author and longtime friend. “Master Han always handled his role as a grand master with a really profound sense of who he was and what he represented. He was an inspiration for his students.”

Born Aug. 25, 1933, in On Chun, near Seoul in what is now South Korea, Han was the youngest of five children. His parents, In Suk Han and Hee Suk Han, made their living farming. During Japan’s occupation of Korea, Han studied the Japanese martial arts kendo and judo in school. Later he earned a black belt in an art known as kwon bup. During the Korean War, he put his study of martial arts on hold and fought with the army.

After his discharge, Han was in Seoul one day and observed Young Sul Qioi performing a demonstration of hapkido, which has been described as the “art of coordinated inner strength.”

Hapkido incorporates powerful kicking techniques and fluid throwing. It is based on the water principles of yielding, circular motion and penetration.

“I was most impressed by its flowing, effortless movements,” Han said in an interview with Martial Arts & Combat Sports magazine in 2001. “Instead of clashing, there were redirection and circular motion … the way of natural movements.”

Han became a student of Choi, considered one of Korea’s best fighting masters, then entered a Buddhist monastery to further develop his martial arts knowledge. In his early days as a teacher, Han trained Korean military personnel and police, as well as Green Berets in the U.S. Army’s Special Forces.

Bong Soo Han moved to the United States in 1967, hoping to spread hapkido in the West. “In order to spread out all over the world, you have to come to the biggest and most powerful nation,” he said in a 1984 interview.

On July 4, 1969, Han gave a demonstration at a park in Pacific Palisades. Laughlin was in the audience that day and later became one of Han’s students. Though Laughlin performed much of his own stunt work in “Billy Jack,” Han performed the more advanced techniques and choreographed fight scenes.

“I saw that and thought, ‘Boy, oh, boy. That’s great,’ and I went over to Han’s dojang and enrolled,” said Hyams, a martial artist who wrote “Zen in the Martial Arts,” which explores the teachings of Han and others.

“Billy Jack” led to other film work, with Han appearing in or coordinating fight scenes in “Force Five,” “Kentucky Fried Movie” and “Cleopatra Jones,” among others.

Han married and later divorced Christen Oh. He is survived by their two children, daughter Susan Han and son Tad Han, both of Santa Monica. In addition, Han is survived by a sister, Ok Su Han of Santa Monica, and son-in-law Kevin Riley of Santa Monica, whom Han considered a son.

Since he opened his first school in the 1960s, Han’s teachings have spread through his International Hapkido Federation, which now consists of nine affiliated schools.

Though his students might have gone to him with the goal of fighting, Han taught them the spiritual and mental dimensions of martial arts.

The most important thing Han was taught was “to know oneself as a human being,” he once said. The most important thing he could teach a student, he said, was “the perfection of character.” In decades of teaching thousands of students, Han promoted only about 100 to black belt. “He held very high standards. It didn’t come easy,” Davis said.

The teacher could throw a 250-pound man easily, yet he was gentle. A charismatic figure, he radiated confidence, calm and security and set an example for what students could obtain through the study of martial arts, Hyams said. Han, a grand master, held the rank of 9th Dan Black Belt.

“There’s a samurai maxim: ‘A man who’s attained mastery of his art reveals it in his every action,'” Hyams said. “And he was a master of his art.”

By Jocelyn Y. Stewart, Times Staff Writer